NYTimes.com:

Do women and men have different brains?

Back

when Lawrence H. Summers was president of Harvard and suggested that

they did, the reaction was swift and merciless. Pundits branded him

sexist. Faculty members deemed him a troglodyte. Alumni withheld

donations.

But

when Bruce Jenner said much the same thing in an April interview with

Diane Sawyer, he was lionized for his bravery, even for his

progressivism.

“My brain is much more female than it is male,” he told her, explaining how he knew that he was transgender.

This

was the prelude to a new photo spread and interview in Vanity Fair that

offered us a glimpse into Caitlyn Jenner’s idea of a woman: a

cleavage-boosting corset, sultry poses, thick mascara and the prospect

of regular “girls’ nights” of banter about hair and makeup. Ms. Jenner

was greeted with even more thunderous applause. ESPN announced it would

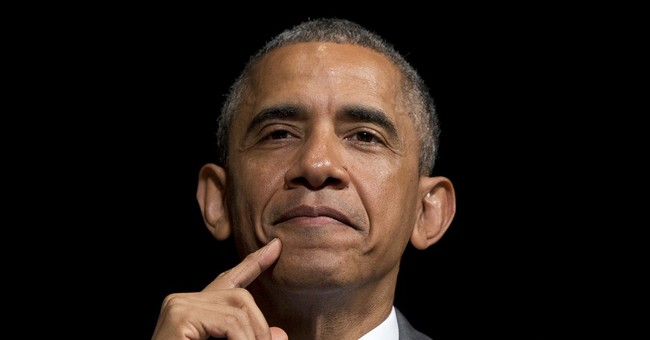

give Ms. Jenner an award for courage. President Obama also praised her.

Not to be outdone, Chelsea Manning hopped on Ms. Jenner’s gender train

on Twitter, gushing, “I am so much more aware of my emotions; much more

sensitive emotionally (and physically).”

A part of me winced.

I

have fought for many of my 68 years against efforts to put women — our

brains, our hearts, our bodies, even our moods — into tidy boxes, to

reduce us to hoary stereotypes. Suddenly, I find that many of the people

I think of as being on my side — people who proudly call themselves

progressive and fervently support the human need for self-determination —

are buying into the notion that minor differences in male and female

brains lead to major forks in the road and that some sort of gendered

destiny is encoded in us.

That’s

the kind of nonsense that was used to repress women for centuries. But

the desire to support people like Ms. Jenner and their journey toward

their truest selves has strangely and unwittingly brought it back.

People

who haven’t lived their whole lives as women, whether Ms. Jenner or Mr.

Summers, shouldn’t get to define us. That’s something men have been

doing for much too long. And as much as I recognize and endorse the

right of men to throw off the mantle of maleness, they cannot stake

their claim to dignity as transgender people by trampling on mine as a

woman.

Their

truth is not my truth. Their female identities are not my female

identity. They haven’t traveled through the world as women and been

shaped by all that this entails. They haven’t suffered through business

meetings with men talking to their breasts or woken up after sex

terrified they’d forgotten to take their birth control pills the day

before. They haven’t had to cope with the onset of their periods in the

middle of a crowded subway, the humiliation of discovering that their

male work partners’ checks were far larger than theirs, or the fear of

being too weak to ward off rapists.

For

me and many women, feminist and otherwise, one of the difficult parts

of witnessing and wanting to rally behind the movement for transgender

rights is the language that a growing number of trans individuals insist

on, the notions of femininity that they’re articulating, and their

disregard for the fact that being a woman means having accrued certain

experiences, endured certain indignities and relished certain courtesies

in a culture that reacted to you as one.

Brains

are a good place to begin because one thing that science has learned

about them is that they’re in fact shaped by experience, cultural and

otherwise. The part of the brain that deals with navigation is enlarged

in London taxi drivers, as is the region dealing with the movement of

the fingers of the left hand in right-handed violinists.

“You

can’t pick up a brain and say ‘that’s a girl’s brain’ or ‘that’s a

boy’s brain,’ ” Gina Rippon, a neuroscientist at Britain’s Aston

University, told

The Telegraph last year. The differences between male and female brains

are caused by the “drip, drip, drip” of the gendered environment, she

said.

THE

drip, drip, drip of Ms. Jenner’s experience included a hefty dose of

male privilege few women could possibly imagine. While young “Bruiser,”

as Bruce Jenner was called as a child, was being cheered on toward a

university athletic scholarship, few female athletes could dare hope for

such largess since universities offered little funding for women’s

sports. When Mr. Jenner looked for a job to support himself during his

training for the 1976 Olympics, he didn’t have to turn to the meager

“Help Wanted – Female” ads in the newspapers, and he could get by on the

$9,000 he earned annually, unlike young women whose median pay was

little more than half that of men. Tall and strong, he never had to

figure out how to walk streets safely at night.

Those are realities that shape women’s brains.